Non-wirewound resistor materials, such as film, foil, and metal oxide, are essential components in modern electronics, offering diverse characteristics tailored to specific applications. These resistors provide enhanced stability, precision, and thermal performance compared to traditional wirewound designs. Understanding the unique properties of these materials is critical for engineers looking to optimize their designs for efficiency and reliability across a wide range of industries.

Introduction to Film Resistors

Film resistors are built either on cylindrical rods or on planar substrates. Usually, the material in the rods and substrates is ceramic in the state of aluminum oxide (alumina), but the glass may occur. Hollow cores exist but are more and more abandoned when sizes are becoming smaller. This design also suffers from drawbacks: the construction is more fragile, and the heat dissipation is poorer than that of a solid core.

Hole mount

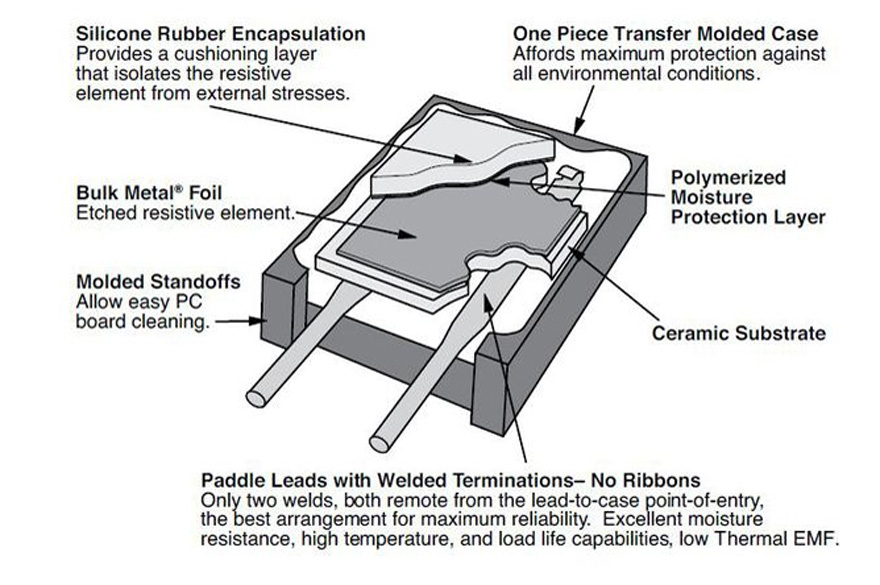

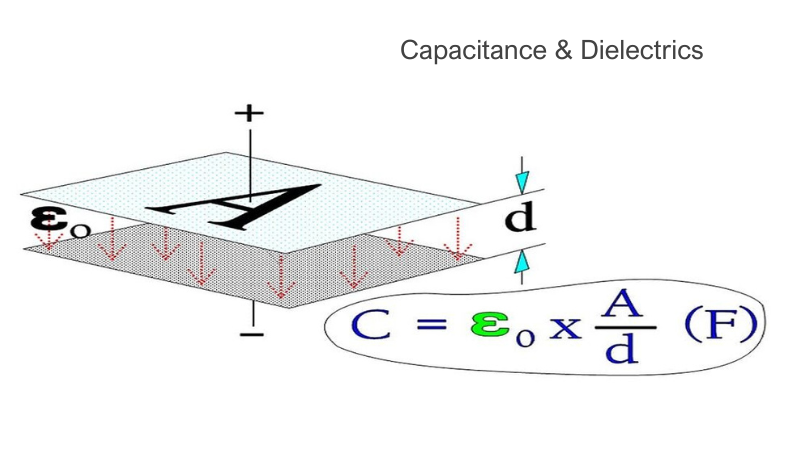

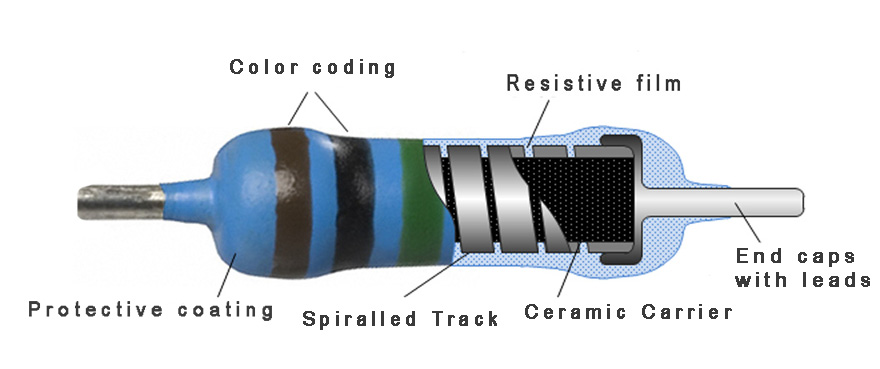

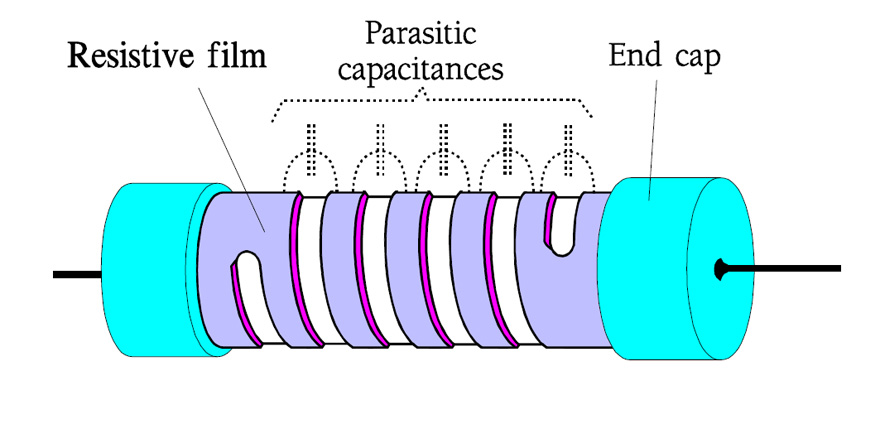

A typical film resistor is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cutaway view of film resistor.

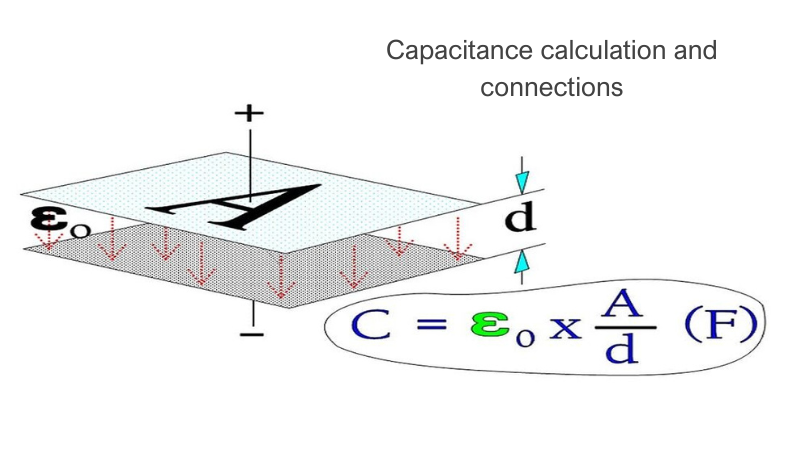

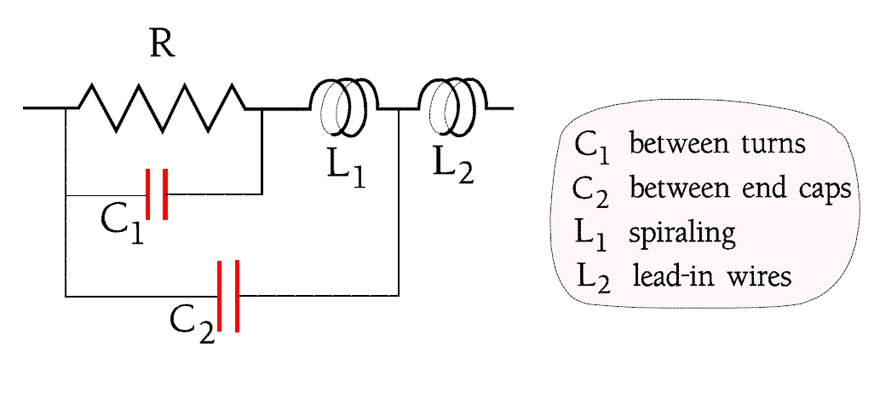

Figure 2: Schematic of a spiraled film resistor.

The film of the cylindrical rods thus is cut in a helical track to a long path, usually with a laser. A more stylized sketch is shown in Figure 2. The pitch of the helix track can be varied in order to increase the resistance of the film. For thick films, an increase of up to 150 times, and for carbon and metal films, up to 1000 times or even more.

As indicated in the figure, a stray capacitance is developed between the turns. Because the turns also constitute a coil the resistor will get a certain inductance. All in all, the spiralling produces a frequency-dependent impedance where the capacitance is dominating.

Film resistors may be approximately classified as follows:

- values < 100Ω are inductive.

- values between 100Ω and 470Ω are practically true resistive.

- values above 470Ω are capacitive.

Figure 3: Equivalent circuit for film resistors.

Fusible and flameproof resistors

A strong overload of carbon and metal film resistors will lead rapidly to an open circuit that, in most cases, is accompanied by a build-up of smoke, glow or even fire. Some manufacturers have developed designs that burn off within certain limits. They are called fusible resistors. The open-circuit conditions are defined in particular power-time diagrams. The limits still must be regarded as “broad”.

If coatings and casings are used that don’t generate or sustain a fire, we talk about flameproof resistors. The drawback with these casings in the past was partly impaired environmental protection and partly a troublesome environmental disadvantage from a recycling viewpoint since they often contain bromine compounds. Modern flameproof resistors have been replaced with bromine-based fire retardants with metal oxide compounds. Check with manufacturer datasheets.

Chips and networks

Film resistors also exist as discrete chips or in so-called resistor networks where they are collected under a common housing.

Load chart Nomogram

The connection between stability, operating time, temperature, power and resistance usually are shown in particular nomographic load charts. Figure 4 shows such a diagram for a sample film resistor. The example reveals how a 1 kΩ resistor working with 0.24 W at an ambient temperature of 80 °C gets a Hot Spot temperature of approximately 137 °C which after 10 000 hours operation produces an expected resistance change of approximately 0.4%. Such a modest change indicates a considerable derating of the nominal power that very well could have been 0.4 or 0.5 W in this example.

Consequently, a nomographic load diagram corresponds only to one type and size (power).

In the nomograph example below you shall start at the actual power on the load axes and draw a horizontal line to the right to the parameter of actual ambient temperature. From that point of intersection, you draw a perpendicular line that crosses the axis for actual Hot Spot temperature and continue to the parameter of actual resistance. There you continue horizontally to the parameter of estimated time of operation. From this point of intersection, you then continue 90° upwards to the axes marked with the corresponding calculated resistance change.

Figure 4: Nomographic load diagram for a fictitious film resistor.

Metal Film / Thin Film

Today, the most dominant type of resistor is the metal film. Sometimes, it is called thin film. From the beginning, precious metals or resistive alloys were evaporated in a vacuum process and then evaporated on ceramic rods. However, the TCR specifications were especially hard to fulfil (TCR = temperature coefficient of resistance). Stability and TCR accuracy took a leap forward when one passed to metal ion bombardment of the rods (so-called sputtering). Today all the techniques have been developed and refined.

The evaporation technique works with both vacuum and chemical volatility processes. Sputtering and ion implanting have become synonymous concepts. The technical progress today motivates the manufacturing of high-precision resistors. We talk about the third generation of metal/thin film resistors.

Common film alloys are nichrome (CrNi) or tantalum nitride (Ta2N), often with additives of aluminum (Al), silicon (Si) or titanium (Ti). The tantalum nitride has very fine low noise characteristics and is superior in hi-fi applications. Generally, metal film resistors keep noise down by means of laser spiralling that, properly utilized, produces even tracks free from irregularities. Noise is discussed in section R1.9.

Occurrence of non-linearity – distortion – is mastered by measurement of the third harmonic distortion and automatic screening, where failing parts not meeting stated requirements are removed from the lot.

Distinctive of the metal films is their thin layers – 50…5000 Å or, 0.005…0.5 μm (0.2 …20 microinches). The thinnest films correspond to the highest resistance values where the film starts approaching molecular thicknesses and, to some extent, deviates from the noise-free conduction capability of metals. Thus the noise is increasingly greater in the high resistance range. Films thinner than 350 Å should be avoided in noise-sensitive designs. Another reason for avoiding them is their extreme sensitivity to moisture-related electrolytic corrosion, especially if the film consists of chromium-nickel alloys. Since the film thickness is not stated in the data sheets, we may obtain certain guidance of where the film is getting too thin for high-reliability applications by dividing the manufactured maximum value by 10. Then, choose the highest manufactured value of the size in question from several serious manufacturers. For example, if the maximum value is 15 MΩ, this rule of thumb gives an upper limit value of 1.5 MΩ. If the application is a dry room environment without large temperature variations (no risk of condensation) and low noise requirements, we may use considerably higher resistive values. But still, we should, both for reliability and, above all, availability reasons, take care not to use the highest manufactured maximum value.

Check with other serious manufacturers where their maximum values are and purchase a little bit below the lowest maximum value.

Also, the relatively thickest films are thin and corrosion-disposed in moisture, especially if they are working with DC loads. A good encapsulation, therefore, is necessary. US MIL components exist with hermetic seals, but they are relatively expensive. Epoxy/plastic molding does not always offer the same good protection as lacquered coverings, at least not if the lacquer is applied in several thin layers. Farthest in, there are one or several – often transparent – coatings of lacquer followed by several layers of coloured lacquer. Here, the Europeans are far ahead. Duplicated production of cheap standard components with multilayer lacquered coverings will probably come rather close to optimum with regard to price and quality.

Another risk zone for metal film resistors is the electrostatic discharge (ESD). The closer the tolerances, the more important part protection against ESD.

Finally, metal film resistors are sensitive to power pulses. The power will warm up the thin resistance track very rapidly. Consequently, also, short pulses may lead to a risk of burning off or too high temperatures that may hazard the stability. Conservative recommendations talk of a maximum of 2 x PR, where PR stands for rated power. At all events, we should not exceed 4 x PR even if the mean power is within specified limits. Single pulses may be much higher, but we have to inquire into every particular case: type, manufacturer, value, environment…

Low ohmic designs

Values below 10 ohms previously have been manufactured so that the ceramic rods are plated with a resistive alloy, in a bath or a burning process, or by electroplating. The plated layer then will become proportionately thick – between 1 and 5 μm (0.04 and 0.2 mils) – and will have a very good pulse power capability. However, tolerances and TC values will be poorer. In the lowest resistance values, there is no spiralling, which will improve the pulse capability further.

Today, some manufacturers have succeeded in producing low ohmic resistors of 0.1 ohm with the sputtering technique. This eliminates the plating technique difficulties with TCR and tolerance but impairs the pulse capability.

Power and precision types

If we load a conventionally power-rated metal film resistor with a higher power, the temperature will rise, and this, in turn, will decrease stability. Thus, power resistors in metal film often have a tolerance of ±5% in the E24 series. Alloys and lacquers have been chosen in order to endure higher operation temperatures.

If we go in the other direction and reduce the power – derate – and lower the maximum permissible ambient temperature, we get a very stable resistor. IEC 115-5 divides in that way the same sizes in different stability classes, from 0.5 to 0.05 %. It’s the same philosophy as behind Figure R2-9 for precision wire-wound resistors. High-stability resistors can be worth producing in fine tolerances and TC values. Thus, the market precision resistors are characterized by low power ratings, fine tolerances, low TCR values, and high stability. Note, however, that TC information is sometimes connected to restrictions in the temperature range. The finer the TC, the more narrow the temperature range.

In order to increase the stability further, high precision components are subjected to ageing processes where one already under manufacture releases prospective changes.

Linear PTC designs

If we choose metal film alloys that bring out the positive TC of the metals – positive temperature coefficient, PTC – we get relatively linear PTC resistors. Values between +2000 and + 6500 ppm/°C are offered. Just as for the wire-wound counterparts, the resistance range is limited upwards.

Mounting

At least 0.5 mm air space or additional insulation should separate the resistors from adjacent metal parts, for example conductive patterns on printed circuit boards.

Metal Foil

Within the metal film technology, there is a particular type of precision resistor made by metal foils by the inventor Vishay Intertechnology, called Bulk metal foil. These resistors exist both in axial and radial designs for hole mount, further as SMDs, networks and power styles, and finally also in PTC designs.

Figure 5 shows a principle cutaway view of a foil resistor from the manufacturer Vishay. The etching pattern is not shown.

The coefficients of the thermal expansion of the resistance alloy and substrate are different. When the alloy foil is firmly attached to the ceramic substrate in a unique way it results in compressive stress on the alloy when the temperature increases. The resistivity of the alloy versus temperature changes is matched with variations of the resistance of the alloy with stress. In other words, by this method, the physical expansion behavior of the foil is forced to follow the considerably lower expansion or shrinkage movements of the substrate at temperature changes. This results in a foil with excellent stability and TCR characteristics. The construction also results in outstanding characteristics of thermal electromotive forces and voltage coefficients.

The foil then is etched to a serpentine or labyrinth pattern, either by means of a photoresistive film, mask and chemical etching (photolithography) or by means of a guided ion beam. Particular, not mold encapsulated styles, can be bought together with trimming tools. By scribing an open-circuit in particular conductance paths the resistance value may be trimmed to extremely fine tolerances. The patterns eliminate much of the inductance that burdens spiralled components.

Since the foils have thicknesses of more than 2.5 μm (0.1 mils) they have excellent pulse resistant characteristics. They don’t suffer from the extreme corrosion sensitivity of thin films either. The disadvantage is that the maximum resistance of metal foil styles will be limited (See Table 1).

The most common failure mode of metal foil resistors is open-circuit in contact joints after temperature changes or of shifts in resistance as debris or weak spots in the resistive path burn out.

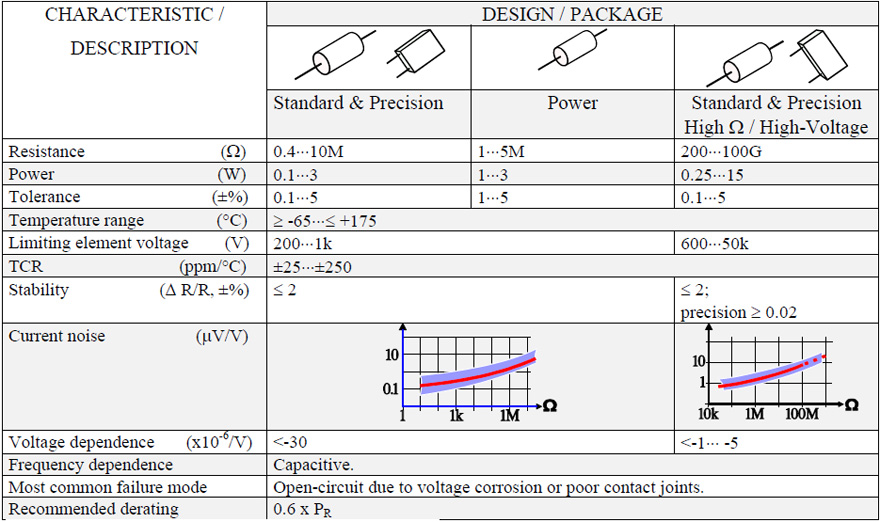

Table 1: METAL FILM & METAL FOIL RESISTORS

Metal Glaze / Thick Film

If we screen print a paste of finely scattered metal particles (for example ruthenium, ruthenium oxide, rhodium, palladium, tantalum-tin) together with glass powder on a ceramic substrate and fire the film until the glass melts, we get a resistive film from some μm up to 25 μm (1 mil) of thickness, a so-called thick film or metal glaze. The substrate has to be chosen with great care in order to constitute an integrated part of the melted glass powder. A variant of the thick film exists in some potentiometers under the name of the cermet. Actually, it is a manufacture connected film that first was put on the market by the manufacturer Beckman Industrial. Today the name cermet is generally recognized.

The film is very environment resistant and has surface resistivities up to 1 MΩ/square, which allows high resistance values in small chip sizes. Here the thick film meets with its dominating application together with its existence in networks. Axial through-hole mounted components are manufactured almost exclusively as high ohmic/high voltage types. Traditional high ohmic resistors in the 100-MΩ range of carbon composition, carbon film or metal oxide designs generally with advantage can be replaced with metal glaze resistors.

After the firing cylindrical bodies are spiraled as shown in Figure R3-1 and R3-2. Plane surfaces are laser trimmed to exact values. The tolerances usually are situated between 1 and 10 % and the TCRs between ±25 and ±300ppm/°C. The closest TCR, ±25 ppm, deserves certain caution because of the risk of drift outside the specification limits.

The conduction mechanism in the metal glaze/ thick film consists of contacts between small metal granules. This leads to considerably more noise than in genuine metal film resistors. Furthermore, the user should be careful with strong pulse loads, at least in the k range. They might give permanent resistance changes due to damaged contact points.

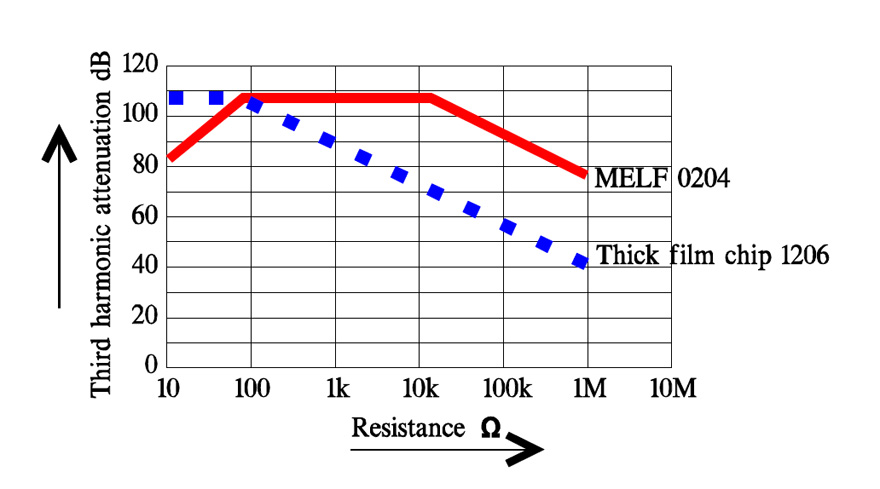

Another phenomenon that characterizes thick film materials more than pure metals is non-linearity. The thick film with its complicated conduction network and countless contact spots suffers from non-linearity at relatively low resistance values. Following diagrams show the difference between thick film and metal film materials in two SMD styles: a metal film “MELF” and a thick film chip.

Figure 6: Examples of third harmonic attenuation in different resistor materials.

Metal Glaze / Thick Film

Metal film resistors have increasingly replaced metal oxide resistors. But, they still have a market in the high ohmic-high voltage range. Precision designs exist in all resistance ranges.

There are different ways of producing resistive metal oxide films. If we heat ceramic rods in a vapor of stannic chloride we get a coating of stannic oxide with good resistive characteristics. The thickness is approximately 1μm (0.04 mils). If we instead use glass that, in a hot state, is extruded in a stannic chloride vapour, it will result in a film of stannic oxide integrated with the glass to form an environment resistive resistance film. It will withstand several hundred per cent overloads with good stability. On the other hand, these resistors are extremely sensitive to stronger power pulses, also of short duration. Another way to produce metal oxide films is to first apply a metal film on the rods and then oxidize the film in oxygen gas.

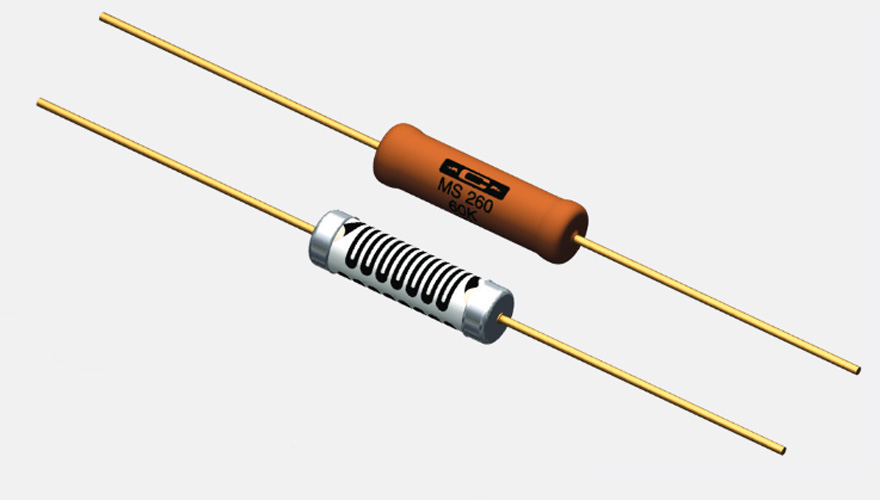

Usually the rods are spiraled conventionally. The lead pattern, however, can be formed in an inductance-limiting serpentine pattern, as shown in Figure 7 from the manufacturer Caddock Electronics, Inc.

The metal oxide film has excellent noise characteristics, which is next to metal films the best. Unlike other films, it does not run the risk of being oxidized at higher temperatures.

It is already oxidized. Thus, hot spot temperatures up to 275 °C are permitted for power resistors. However, the user needs to check with the manufacturer’s data sheet about how much the chosen type can stand. It varies. The power types are sometimes supplied with cooling plates integrated with the housing.

Certain metal oxide films are also suited for high voltage or high ohmic types, the latter in values up to at least 100 GΩ.

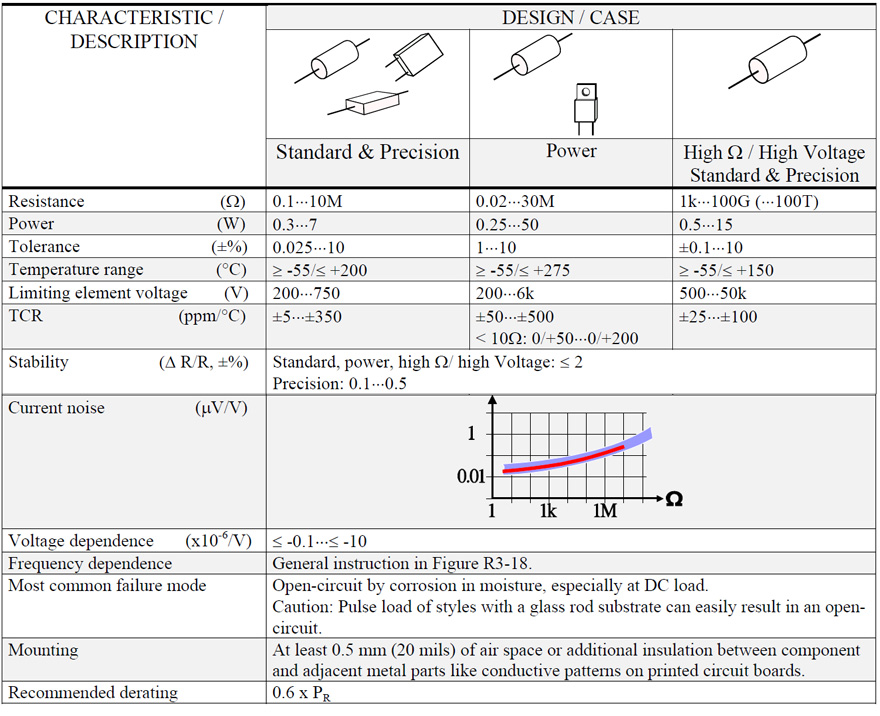

Table 3: METAL OXIDE (“Metox”) RESISTORS

Author:

EPCI | Bringing Passive Professionals Together